STROKE IN CHILDREN

Cerebral infarction and cerebral hemorrhage in children are being diagnosed more frequently and promptly in recent years. Their incidence has been reported to be between 1.2 and 13 cases per 100,000 children per year. Hemorrhagic stroke is more frequent in children than it is in adults. Cerebral sinovenous thrombosis is not included in some of these statistics. Not included also are germinal matrix hemorrhage and periventricular white matter necrosis, which are special types of hemorrhagic stroke in premature neonates.

ARTERIAL ISCHEMIC STROKE (AIS)

The pathophysiology and evolution of AIS in children is no different from adults. Most cases present with hemiparesis, seizures, and lethargy. Childhood AIS is fatal in 3% of cases and causes significant permanent neurological disability in the majority of cases. It has different causes than adult AIS, and its diagnosis and classification are based on clinical and radiological criteria. About half of AIS cases have a known predisposing condition. Many patients have previous head and neck trauma or a mild infection. The most common risk factors of childhood AIS are listed below and some entities are briefly discussed further on.

Autoimmune vasulitis Infectious and post-infectious angiopathy (meningitis, fungal vasculitis, post-varicella arteritis) Angiopathies associated with metabolic disorders (Fabry disease, homocystinuria, hyperhomocysteinemia) |

Transient (focal) cerebral arteriopathy (TCA-FCA). This common monophasic childhood cerebral arteriopathy affects the distal internal carotid and proximal middle and anterior cerebral arteries causing segmental narrowing and irregularity of the vascular lumen, leading, most commonly, to basal ganglia infarcts. The pathological basis of TCA is not known. Some cases are preceded by varicella zoster virus (VZV) infections, suggesting that TCA is post-varicella arteritis. VZV causes an arteritis involving proximal branches of cerebral arteries during the acute phase of the infection or following reactivation. This arteritis may lead to narrowing or occlusion of the affected vessels. TCA appearing within 12 months after varicella is called post-varicella arteriopathy. It has been suggested that infections by other agents (Borrelia burgdorferi, mycoplasma, parvovirus, CMV) is responsible for TCA without a history of VZV.

Arterial dissection (dissecting aneurysm) is a common cause of AIS in children. It occurs spontaneously or after mechanical injury to the head and neck or intra-oral trauma. The injury may be significant or minor and in some case no history of trauma is elicited. Genetic connective tissue disorders such as Ehlers-Danlos and Marfan syndrome may play a role in the pathogenesis of some cases. The classic angiographic findings are a double lumen, intimal flap, or pseudo-aneurysm. The dissection is a hematoma that develops in the vessel wall, most commonly between the internal elastica and the media. The hematoma lifts the intima and elastica and collapses the vascular lumen. Less frequently, the hematoma develops between the adventitia and the media, in which case, in addition to occluding the vessel, it may rupture externally causing headache.

Moyamoya (a puff of smoke) describes the angiographic appearance of a rich collateral network that develops in some cases of slowly evolving stenosis or occlusion of large cerebral arteries. Such changes (Moyamoya syndrome) are seen in conditions with a defined etiology such as NF1, sickle cell disease, radiation, and trisomy 21, and occur also in Asian patients without a specific underlying cause (Moyamoya disease).

Vasculitis: Systemic vasculitides (polyarteritis nodosa, Wegener’s granulomatosis, Churg-Strauss arteritis, temporal arteritis, and others) affect the CNS infrequently. The same is true of vasculitis developing in the background of lupus erythematosus and other systemic inflammatory and rheumatological diseases. Vasculitis may also be a component of bacterial, fungal, and viral infections of the CNS. Primary angiitis of the CNS (PACNS) involves the brain only and is defined as a condition causing neurological and psychiatric deficits with evidence of angiitis by imaging or biopsy, in absence of systemic vasculitis, collagen-vascular disease, or infection.

Nonprogressive angiography-positive PACNS is a monophasic angiitis that involves the distal internal carotid and proximal middle and anterior cerebral arteries and causes AIS. It is also referred to as transient cerebral arteriopathy and is associated with varicella infection in some instances (see above). Progressive angiography-positive PACNS is a chronic, progressive angiitis that affects proximal and distal vessels and causes AIS and inflammatory lesions. | |

The pathology in angiography-negative PACNS is intramural and perivascular mononuclear infiltrates and must be distinguished from “perivascular cuffing” which is commonly seen in viral infections and MS. The vascular pathology in angiography-positive PACNS has not been studied but is presumed to be inflammatory also.

PERINATAL AND FETAL STROKE

Perinatal AIS (AIS in utero or before 28 days of age) is much more frequent than AIS occurring later in childhood. It affects 1:3000 liveborn infants, close to the incidence of adult large vessel ischemic stroke. In the acute phase, it may be asymptomatic or present with seizures. Later, patients develop hemiparesis and other deficits, including intellectual disability, behavior disorders, and epilepsy. The cause of perinatal AIS is unknown in most cases. Risk factors include fetal /neonatal and maternal thrombophilia (the relative risk of stroke in infants who are heterozygotes for factor V Leiden is 4.2%) usually combined with multiple other factors; placental pathology (chorioamnionitis, infarcts, fetal thombotic vasculopathy); genetic disorders (COL4A1 mutation associated with porencephaly); cardiac causes including procedures; infection, especially meningitis; and pregnancy complications.

Fetal stroke, defined as stroke occurring between 14 weeks of gestation and the onset of labor, is more frequently hemorrhagic than either pediatric or adult stroke. Risk factors include alloimmune thrambocytopenia and other maternal bleeding disorders, placental thrombosis associated with inherited and acquired thrombophilia, twin pregnancy, especially monozygotic twins, and maternal trauma. The same risk factors that cause neonatal and pediatric stroke account also for fetal stroke but no specific etiology is found in 50% of cases. The end result of fetal stroke may be a fluid filled cavity (porencephaly). Some cases of schizencephaly and polymicrogyria probably represent fetal strokes. Germinal matrix hemorrhage and periventricular hemorrhagic infarction, special forms of hemorrhagic stroke in premature infants, are described elsewhere.

HEMORRHAGIC STROKE

About half of all cases of stroke in children are hemorrhagic strokes. The leading causes are vascular anomalies (arteriovenous malformations, arterial [saccular] aneurysms, cerebral cavernous malformations) and less frequently other factors (coagulopathies, brain tumors, sickle cell disease). Patients present with headache, mental status change, nausea, vomiting, focal deficits, and seizures. The pathology and pathogenesis of hemorrhagic stroke in children is similar to adults.

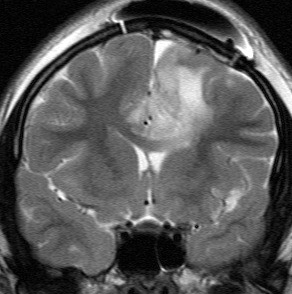

Sinovenous thrombosis (SVT) affecting the superior sagittal sinus and its tributaries causes bilateral parasagittal hemorrhagic infarcts. Thrombosis of the straight sinus, great vein of Galen, and deep veins causes thalamic infarction. SVT occurs in all age groups and frequently has a multifactorial etiology. It is common in neonates and young infants with sepsis, meningitis, and dehydration. In this setting, it presents nonspecifically with irritability, seizures, and lethargy. In older children with underlying thrombophilia, SVT frequently presents with signs and symptoms of “idiopathic intracranial hypertension" (pseudotumor cerebri), i.e., headache, papilledema, altered consciousness, and seizures.

Further Reading

- Mackay MT, Wiznitzer M, Benedict SL, et al Arterial Ischemic Stroke Risk Factors: The International Pediatric Stroke Study. Ann Neurol 2011;69:130–140. PubMed

- Lyle CA, Bernard TJ. Goldenberg NA. Childhood Arterial Ischemic Stroke: A Review of Etiologies, Antithrombotic Treatments, Prognostic Factors, and Priorities for Future Research. Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis 2011; 37: 786-93. PubMed

- Steinlin M. A Clinical Approach to Arterial Ischemic Childhood Stroke: Increasing Knowledge over the Last Decade. Neuropediatrics 2012;43:1–9. PubMed

- Gowdie P Twilt M, Benseler SM. Primary and Secondary Central Nervous System Vasculitis. J Child Neurol 2012;27(11) 1448-1459. PubMed

Posted: February, 2013