THE NORMAL CSF

The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is produced from arterial blood mainly by the choroid plexuses of the lateral and fourth ventricles by a combined process of diffusion, pinocytosis and active transfer. A smaller amount of CSF is also produced by ependymal cells and is derived from the interstitial fluid (ISF) of brain tissue. CSF acts as a cushion that protects the brain and spinal cord from shocks. It also plays an important role in the homeostasis and metabolism of the central nervous system. It transports nutrients and other substances into the brain and serves as a “sink” that receives products generated by brain catabolism and synaptic function.

The choroid plexus consists of tufts of capillaries with thin fenestrated endothelial cells. These are covered by modified ependymal cells with bulbous microvilli. The epithelial cells of the choroid plexus have tight junctions and form the blood-CSF barrier (BCSFB), which controls the movement of water and solutes into the CSF. The apical surface of choroid plexus epithelial cells contains Aquaporin1 (AQP1), a membrane protein (water channel) that facilitates movement of water across cell membranes. The choroid plexus epithelial cells contain also carbonic anhydrase, a hydrolytic metalloenzyme that is involved in CSF secretion. The total volume of CSF in the adult ranges from140 to 270 ml. The volume of the ventricles is about 25 ml. CSF is produced at a rate of 0.2 - 0.7 ml per minute or 600-700 ml per day.

CSF from the lumbar region contains 15 to 45 mg/dl protein (lower in childen) and 50-80 mg/dl glucose (two-thirds of blood glucose). Protein concentration in cisternal and ventricular CSF is lower. Normal CSF contains 0-5 mononuclear cells. The CSF pressure, measured at lumbar puncture (LP), is 100-180 mm of H2O (8-15 mm Hg) with the patient lying on the side and 200-300 mm with the patient sitting up.

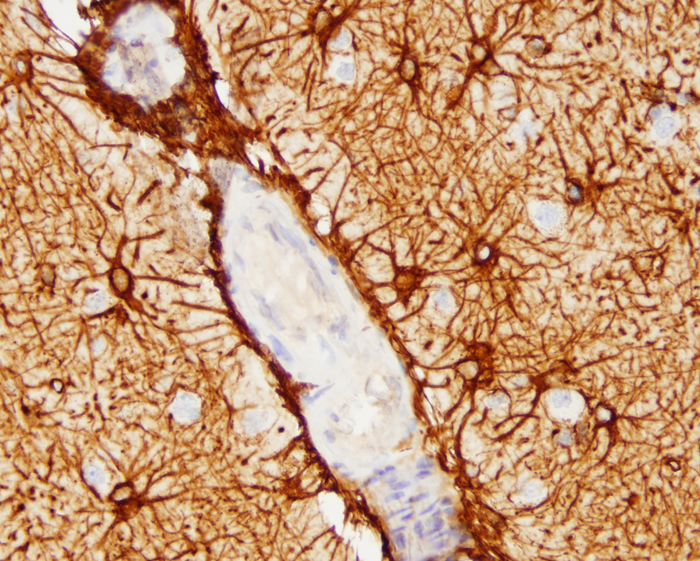

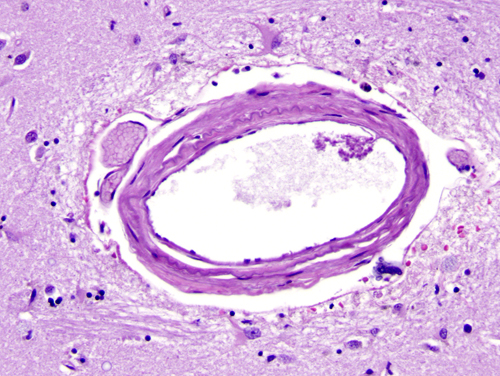

Unlike other organs and tissues, the endothelial cells that line brain capillaries have no fenestrations or pinocytotic (transportation) vesicles and have tight

and adherens junctions that almost fuse adjacent endothelial cells. Moreover, these endothelial cells have different receptors and ion channels on their surface facing the lumen than on the surfaces facing the brain, an arrangement that facilitates transcellular transport. This anatomy is the basis of the blood-brain

barrier (BBB). The endothelial cells are surrounded by a basement membrane made up of collagens, laminins, and proteoglycans. A discontinuous layer of pericytes are embedded in this basement membrane. Astrocytic processes rich in Aquaporin 4 (AQP4) cover the capillaries. The space between them and the capillary basement membrane contains a few perivascular macrophages and rare lymphocytes that cross the BBB (passing through endothelial cells rather than between them) and survey this space. The same types of cells are present in the perivascular (Virchow-Robin) space (see below). Brain endothelial cells do not express leukocyte adhesion molecules (LAMs) on their luminal surface and this limits the entry of leukocytes into brain tissue. In non-diseased states, no immune cells or molecules are found deeper in brain interstitial space, resulting in an “immune privileged” status. During development, astrocytes induce brain endothelial cells to develop in this special leak-proof fashion.

The BBB separates plasma from the interstitial space of the CNS and is key to maintaining homeostasis in the CNS. It controls the traffic of molecules, including ions and water in and out of the brain and plays an important role in supplying the brain with nutrients and getting rid of waste and toxic products. The ability to exclude certain substances from brain interstitial space has to do not only with the vascular anatomy, but also with lipid solubility and selective transcellular transport by endothelial cells. Lipophilic compounds cross the BBB easier than hydrophilic ones do, and small lipophilic molecules such as O2 and CO2 diffuse freely. Hydrophilic substances can only get across brain capillaries through endothelial cells rather than between them. Some hydrophilic molecules, including glucose and amino acids, enter endothelial cells with the help of transporters, and larger molecules, including proteins, enter via receptor-mediated endocytosis and exit along the opposite surface by exocytosis. GLUT1 is the glucose transporter. The ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters are important for transport of lipophilic substances and efflux of toxic metabolites. The BBB protects the brain from toxic substances but also impedes the entry of drugs. Circulating leukocytes enter the brain by passing through endothelial cells rather than between them. Astrocytes cover almost the entire surface of brain capillaries; they are interposed between the vasculature and neurons thus linking neuronal activity to BBB function. Hypertonic stimuli and chemical substances including glutamate and certain cytokines can open the BBB. Astrocytic processes express Aquaporin 4, another water channel that facilitates transport of water.

A wide variety of disorders including stroke,

trauma, CNS infections, demyelinative diseases,

metabolic disorders, degenerative diseases,

and malignant brain tumors are associated with

BBB dysfunction. The common end result of BBB

dysfunction in many of these disorders is increased

vascular permeability leading to vasogenic

edema. For instance, blood vessels in

glioblastom and other malignant brain tumors do not have

tight junctions, explaining the fluid leakage and

cerebral edema that accompanies these tumors. Cytokines

generated during infectious and inflammatory processes

enhance transmigration of circulating leukocytes

and may even loosen tight junctions, thus facilitating

the migration of inflammatory cells into the brain.

HIE disrupts the BBB. More subtle BBB dysfunction

may result in impaired glucose transport and accumulation

of Aβ.

The interstitial space of the brain is separated from the ventricular CSF by the ependymal lining and from the subarachnoid CSF by the glia limitans. The glia limitans is a thick layer of interdigitating astrocytic processes with an overlying basement membrane. This layer seals the surface of the CNS and dips into brain tissue along the perivascular space (see below). External to it is the pia matter, a thin layer of connective tissue cells with a small amount of collagen. The ependymal barrier is far more permeable than the BBB.

The major cerebral arteries and veins traverse the subarachnoid space and penetrate into the brain, where they branch into smaller vessels and eventually capillaries. Capillaries are in contact with astrocytic processes. Vessels larger than capillaries are separated from the surrounding brain tissue by a space (the perivascular or Virchow-Robin space), which is an extension of the subarachnoid space. The perivascular space is a component of the “glymphatic”-glial lymphatic- system (analogous to the lymphatic system of the body) which facilitates exchange of molecules between the CSF and the ISF of the brain. CSF flows into brain tissue at the periarterial space, mixes with ISF in brain tissue and effluxes from brain tissue into the CSF along perivenous spaces. It is thought that cardiac pulsations facilitate the exchange of substances between the ISF and the CSF. The glymphatic system helps rid the brain of waste products and maintains homeostasis. Such products include beta-amyloid and tau protein. Thus, the glymphatic system may be important in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease and chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

The outer surface of this perivascular space (PVS) is formed by the glia limitans. The inner surface is the vascular basement membrane. Postcapillary venules are also surrounded by a PVS. The PVS that surrounds postcapillary venules is the portal of entry of leukocytes into the brain in the normal state and during inflammation. Circulating monocytes and lymphocytes normally traverse postcapillary venules and enter the PVS. In the course of inflammation, such as MS, this entry is increased because of leukocyte interactions with inflamed endothelial cells. Furthermore, leukocytes penetrate the glia limitans and enter into the CNS. The latter move is facilitated by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) produced by macrophages, which loosen the glia limitans.

ABNORMALITIES OF CSF

Blood: Blood may be spilled into the CSF by accidental puncture of a leptomeningeal vein during entry of the LP needle. Such blood stains the fluid that is drawn initially and clears gradually. If it does not clear, blood indicates subarachnoid hemorrhage. Erythrocytes from subarachnoid hemorrhage are cleared in 3 to 7 days. A few neutrophils and mononuclear cells may also be present as a result of meningeal irritation. Xanthochromia (blonde color) of the CSF following subarachnoid hemorrhage is due to oxyhemoglobin which appears in 4 to 6 hours and bilirubin which appears in two days. Xanthochromia may also be seen with hemorrhagic infarcts, brain tumors, and jaundice.

Increased inflammatory cells (pleocytosis) may be caused by infectious and noninfectious processes. Polymorphonuclear pleocytosis indicates acute suppurative meningitis. Mononuclear cells are seen in viral infections (meningoencephalitis, aseptic meningitis), syphilis, neuroborreliosis, tuberculous meningitis, multiple sclerosis, brain abscess and brain tumors.

Tumor cells indicate dissemination of metastatic or primary brain tumors in the subarachnoid space. The most common among the latter is medulloblastoma. They can be best detected by cytological examination. A mononuclear inflammatory reaction is often seen in addition to the tumor cells.

Increased protein: In bacterial meningitis, CSF protein may rise to 500 mg/dl. A more moderate increase (150-200 mg/dl) occurs in inflammatory diseases of meninges (meningitis, encephalitis), intracranial tumors, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and cerebral infarction. A more severe increase occurs in the Guillain-Barré syndrome and acoustic and spinal schwannoma. In multiple sclerosis, CSF protein is normal or mildly increased, but there is often an elevation of IgG in CSF, but not in serum, expressed as an elevation of the CSF IgG/albumin index (normally 10:1). In addition, 90% of MS patients have oligoclonal IgG bands in the CSF. Oligoclonal bands are also seen occasionally in some chronic CNS infections. The type of oligoclonal bands is constant for each MS patient throughout the course of the disease. Oligoclonal bands occur in the CSF only (not in the serum). These quantitative and qualitative CSF changes indicate that in MS, there is intrathecal immunoglobulin production. In addition, the CSF in MS often contains myelin fragments and myelin basic protein (MBP). MBP can be detected by radioimmunoassay. MBP is not specific for MS. It can appear in any condition causing brain necrosis, including infarcts.

Low glucose in CSF is seen in suppurative, tuberculous and fungal infections, sarcoidosis, and meningeal dissemination of tumors. Glucose is consumed by leukocytes and tumor cells.

CSF BIOMARKERS

Alzheimer's disease (AD). In AD, total CSF beta amyloid (Aβ) is not significantly different from controls but Aβ42 is decreased probably because it is deposited in plaques and is not available in a diffusible form. Total-tau (t-tau) and phosphorylated tau (p-tau) are both increased in AD. Tau is an intracellular protein and p-tau is a component of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). Their increase in AD is thought to reflect neuronal death with release of tau into the extracellular space. T-tau is also increased in other conditions with neuronal death including Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease(CJD), however, p-tau is not elevated in CJD presumably because there are no NFTs in that condition.

Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease. The most widely used CSF biomarkers for CJD are 14-3-3-protein and Real-Time Quaking-induced Conversion (RT-QuIC). The 14-3-3 proteins (the name derives from their electrophoresis pattern) are a group of proteins with diverse regulatory functions present in all cells. Elevated CSF 14-3-3 in a patient with progressive dementia of less than 2 years' duration is a strong indicator of CJD. However, 14-3-3 is also elevated in patients with acute stroke, encephalitis, and other conditions with extensive brain damage and thus does not rule out CJD. RT-QuIC replicates prion formation in vitro and is nearly 100% specific for CJD.

In the course of traumatic brain injury (TBI), proteins from injured neurons and glial cells are released in the interstitial space and CSF and, because of damage of the BBB, make their way into the blood. Detection of these products in CSF or serum in the early phases of TBI would be very helpful, especially because imaging studies may be inconclusive. Several such markers have been considered. Some of these are present in settings other than TBI. The most promising are the neuronal enzyme Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1) and the astrocytic intermediate filament protein glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). Other biomarkers such as neuron specific enolase and S100B protein are elevated in TBI but are not specific because they are found in tissues outside the CNS.

CSF AND INTRACRANIAL HYPERTENSION

The rigid skull contains the brain, intravascular blood and CSF. When the volume of one of these components increases, the other two adjust to this change up to a point. When intracranial pressure (ICP) exceeds cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP), cerebral blood vessels are squeezed shut and cerebral ischemia ensues. Such a situation occurs as a result of brain tumors and arises also following large ischemic strokes, traumatic brain injury, and cerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Elevation of ICP may also result from increased CSF volume such as hydrocephalus. Most cases of hydrocephalus are caused by obstruction of CSF flow-most frequently from brain tumors and aqueductal lesions. Nonobstructive hydrocephalus may be caused by decreased CSF absorption, such as in sinovenous thrombosis and conditions that cause marked elevation of CSF protein, such as the Guillain-Barré syndrome, and, rarely, by CSF oversecretion by choroid plexus tumors. (see also Hydrocephalus) .Elevated ICP with no other apparent pathology is also thought to be the cause of

Further Reading

- Ballabh P, Braun A, Nedergaard M.

The blood-brain barrier: an overview. Structure, regulation,

and clinical implications. Neurobiol

Dis 2004;16:1-13. PubMed

- Owens T, Bechman I, Engelhardt B. Neurovascular Spaces and the Two Steps to Neuroinflammation. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2008; 67:1113-21. PubMed

- Aluise CD, Sowell RA, Butterfield DA. Peptides and Proteins in Plasma and Cerebrospinal Fluid as Biomarkers for the Prediction, Diagnosis, and Monitoring of Therapeutic Efficacy of Alzheimer's disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 2008;1782:549-58. PubMed.

- Benarroch E E. Blood– brain barrier. Recent developments and clinical correlations. Neurology 2012;78:1268-76. PubMed

- Michetti F, Corvino V, Geloso MC, et al The S100B protein in biological fluids: more than a lifelong biomarker of brain distress. J Neurochem. 2012 Mar;120(5):644-59. PubMed

- Daneman R. The Blood–Brain Barrier in Health and Disease. Ann Neurol 2012;72:648–672 PubMed

- Raper D, Louveau A, Kipnis J. How Do Meningeal Lymphatic Vessels Drain the CNS? Trends Neurosci. 2016 Jul 23. pii: S0166-2236(16)30071-6. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2016.07.001. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed

- Bogoslovsky T, Gill J, Jeromin A, et al. Fluid Biomarkers of Traumatic Brain Injury and Intended Context of Use. Diagnostics 2016, 6, 37; doi:10.3390/diagnostics6040037 PubMed

Updated: January, 2023