PROGRESSIVE MUSCULAR DYSTROPHIES

Muscular dystrophies are genetically transmitted diseases characterized pathologically by degeneration and loss of myofibers and clinically by inexorably progressive weakness and, many of them, by elevated CK. The pattern of weakness, tempo of evolution, and mode of inheritance vary among different dystrophies. Over 30 genes causing muscular dystrophy are known presently. Muscular dystrophies are clinically classified into the following groups:

| Dystrophinopathies (Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies) |

| Limb-Girdle dystrophies |

| Myotonic dystrophy |

| Facioscapulohumeral and scapuloperoneal dystrophy |

| Oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy |

| Distal myopathies |

| Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy |

| Congenital muscular dystrophies |

Some of these groups contain several entities with different inheritance patterns. The most common muscular dystrophy in children is Duchene muscular dystrophy. In adults, the most common dystrophies are myotonic dystrophy and the limb girdle dysytrophies. The molecular pathogenesis and the basis for the genotypic and phenotypic diversity of muscular dystrophies are now beginning to be understood. The key structure in muscular dystrophies is the muscle membrane (see image).

Most muscular dystrophies are due to break down of the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex, a network of fibrous proteins that bind myofibers to the matrix and stabilize the sarcolemma during contraction and relaxation. Some of these proteins are located in the muscle fiber just inside the sarcolemma (dystrophin); others are embedded in the sarcolemma (sarcoglycans); and others are located in the basement membrane outside the sarcolemma (alpha-dystroglycan, merosin). Loss of the integrity of this network causes stress fractures of the sarcolemma to develop during muscle contraction. Influx of calcium through these breaks activates proteolytic enzymes leading to autodigestion of the sarcoplasm (myonecrosis). Defects of dystrophin cause the Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies. Abnormalities of sarcoglycans cause some limb girdle dystrophies. Deficiency of basement membrane proteins such as a2 laminin results in congenital muscular dystrophy. Based on these insights, the phenotypic classification is being replaced by a genetic-molecular classification. For instance, Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies are dystrophinopathies, several limb-girdle dystrophies are sarcoglycanopathies, etc. The clinical, pathological, and molecular aspects of the most common dystrophies are briefly described below.

DYSTROPHINOPATHIES

Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies (DMD-BMD) are caused by mutations of dystrophin, the largest known human gene, located on chromosome Xq21. They are transmitted in an X-linked pattern, i.e. from mother to son. Mothers and daughters are carriers. They have one normal and one abnormal copy of the gene. Male children who inherit the defective copy develop full blown disease. In DMD, dystrophin is absent. In BMD, it is severely reduced and of an abnormal molecular structure. The abnormality can be demonstrated by treating sections of muscle with antibodies to dystrophin (see figure above). In normal muscle, all muscle fibers show a strong reaction along the sarcolemma. In DMD (left), no reaction is seen. DMD muscle stained with antibodies to other membrane proteins such as spectrin (right) shows a normal reaction. In BMD, parts of muscle fibers have dystrophin, and other parts do not. The female carriers of DMD have a mixed population of myofibers, some with dystrophin and some without.

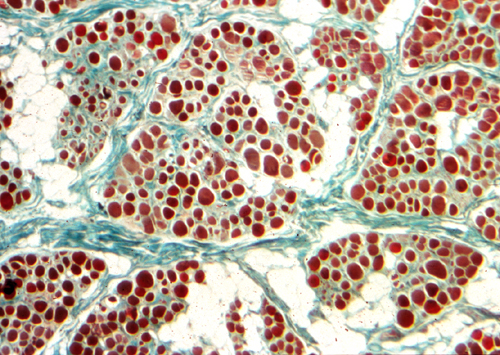

The key pathology of DMD is myonecrosis. At an early phase, necrotic fibers appear homogeneous and deeply eosinophilic. Macrophages then enter necrotic myofibers and remove the debris. Breaks of the sarcolemma allow also CK and other intramuscular proteins to leak out into the interstitial fluid and serum in massive amounts. Myofibers are huge cells. The membrane changes and myonecrosis in dystrophinopathies do not involve the entire muscle fiber, but only parts of it. Myonuclei in unaffected segments divide, activate synthesis of new myofilaments and repair the damage. However, because of the inherent molecular defect, repair is incomplete and cannot keep up with necrosis. Gradually muscle is lost, causing severe weakness. Myonecrosis triggers inflammation. Inflammatory cytokines activate fibroblasts which lay down extracellular matrix proteins. This leads to fibrosis that permeates muscle and causes stiffness and contractures, major causes of disability in DMD. Lost muscle is replaced by fat.

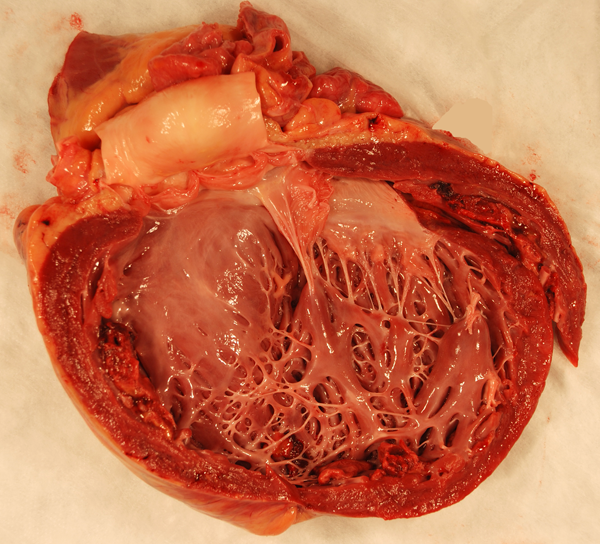

These changes are most severe in DMD in which clinical abnormalities begin in early childhood. At an early stage, some muscles, especially the calves, may appear large (pseudohypertrophy) due to compensatory hypertrophy of non-affected myofibers and increased fat. As the disease progresses, muscle is gradually lost. Patients are usually confined to a wheelchair by 10-12 years. Treatment with prednisone prolongs ambulation by 2-4 years by some poorly understood mechanism. Death usually occurs by the end of the second decade due to respiratory insufficiency and other complications. In BMD, symptoms begin later and the disease is more protracted. Some patients have a nearly normal lifespan. Dystrophin mutations cause also dilated cardiomyopathy. Twenty percent to 40% of females with dystrophin mutations have mild muscle disease or a dilated left ventricle. Even if asymptomatic, they often show mild elevation of CK and subtle changes in the muscle biopsy.

DMD patients have also cognitive impairment and behavioral abnormalities. Dystrophin is present in cortical neurons and Purkinje cells. Autopsy and routine MRI studies in DMD patients show no apparent abnormalities. However, quantitative MRI analysis shows reduced gray matter volume, and diffusion tensor imaging shows white matter changes that suggest reduced fiber density and altered structure. These findings suggest that dystropin mutations affect also brain structure and may account for the clinical abnormalities. The CNS changes are not progressive and probably occur during brain development.

The key laboratory abnormality of DMD and BMD is severe CK elevation. Because the fibers of each motor unit are destroyed gradually, the EMG shows low voltage and short duration motor unit potentials or polyphasic potentials corresponding to residual myofibers within each motor unit. The muscle biopsy shows myonecrosis, phagocytosis of necrotic fibers, regeneration, and non-specific structural changes (central nuclei, split fibers, atrophic and deformed fibers). Increased endomysial connective tissue and fat are also seen. In BMD, the changes are milder. In a 5- year-old boy with proximal weakness, pseudohypertrophy of the calves, a CK of 6,000 and the above biopsy findings, the diagnosis is hardly in doubt. Dystrophinopathy can be confirmed by immunohistochemistry and DNA analysis. The same methods can be used for carrier detection. Because dystrophin is also present in myocardial fibers, a similar process gradually damages the myocardium causing a clinically dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM). DCM develops late in the course of the disease but once begun, progresses rapidly and is the cause of death in 20% of DMD and 50% of BMD patients. Some individuals with dystrophin mutations have DCM but no skeletal myopathy (DMD-associated DCM).

LIMB GIRDLE MUSCULAR DYSTROPHIES

The limb-girdle muscular dystrophies (LGMDs) are a heterogeneous group of autosomally inherited dystrophies that are characterized by a shoulder- and pelvic-girdle pattern of weakness. There are 34 subtypes of LGMD recognized, 26 autosomal recessive (LGMD2) and 8 autosomal dominant (LGMD1). They are caused by mutations of genes that encode diverse proteins that are important for sarcolemmal integrity or are involved in muscle structure and function in other ways, including dysferlin, caveolin-3, sarcoglycans, and a-dystroglycan. The most common mutation involves calpain-3, a protease that is important for sarcomere remodeling. As a group, the LGMDs are less frequent than the dystrophinopathies, myotonic dystrophies, and facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. Although they share the limb-girdle pattern of weakness, they are clinically diverse and overlap with dystrophinopathies, congenital myopathies, congenital muscular dystrophies, metabolic myopathies, and other muscle diseases. Most LGMDs are milder clinically than dystrophinopathies, i.e., they begin in adolescence or adulthood and have a slower progression. However, a subset of autosomal recessive LGMDs caused by deficiencies of sarcoglycans is phenotypically similar to DMD and has been called “severe childhood autosomal recessive muscular dystrophy” (SCARMD). The muscle biopsy in the LGMDs shows myopathic changes of varying severity (myonecrosis, nonspecific structural changes such as split fibers and internal nuclei, myofiber atrophy, and endomysial fibrosis). Some LGMDs, especially the calpainopathies, show also interstitial inflammation, including eosinophils, and may be confused with inflammatory myopathy.

CONGENITAL MUSCULAR DYSTROPHIES (CMDs)

CMDs are a group of rare muscle diseases that present at birth or soon after with hypotonia, weakness, and developmental delay, similar to the congenital myopathies. Contractures develop early in some CMDs. Unlike muscular dystrophies and similar to congenital myopathies, CMDs are nonprogressive and patients are left with static, though in some cases severe muscle disease. CK is high in some and minimally elevated or normal in others. The muscle biopsy shows nonspecific findings, initially myofiber atrophy and later myofiber loss with fibrosis and fat replacement. The biopsy findings may not correlate with the clinical severity. The differential diagnosis of neonatal hypotonia includes SMA, CMD, and congenital myopathy. With the main finding of myofiber atrophy, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish SMA from CMD In a very young infant. Some CMDs are associated with severe CNS abnormalities. CMDs are genetic diseases; most are autosomal recessive. The main CMDs are:

Merosin-deficient CMD, due to deficiency of α-laminin (merosin), a component of the basal lamina of myocytes and other cells. This CMD is associated with white matter abnormalities.

Ullrich CMD, due to deficiency of Collagen VI, also an extracellular matrix component.

CMDs due to abnormal glycosylation of α-dystroglycan, a dystrophin-associated protein. This group includes Fukuyama CMD, which is common in Japan, Muscle-Eye-Brain (MEB) disease, described in Finland, and Walker-Warburg syndrome (WWS). The WWS is the most severe condition among the CMDs and is associated with lissencephaly. Dystroglycan is also expressed in brain tissue, and is important for the normal migration and layering of cortical neurons.

MYOTONIC DYSTROPHY

Myotonic Dystrophy is an autosomal dominant muscular dystrophy characterized by weakness and stiffness, more pronounced in facial and distal muscles, and by increased muscle excitability. Atrophy and weakness of facial muscles, ptosis, and frontal baldness produce a characteristic facial appearance. Myotonia (prolonged muscle contraction) occurs spontaneously or is elicited by voluntary activity or by mild stimulation, such as tapping on a muscle (percussion myotonia). The EMG shows characteristic repetitive discharges. In many cases, a handshake is enough to establish the diagnosis (the myotonic patient cannot let go). Symptoms appear in adolescents or young adults, but no age is spared. At times, congenital myotonic dystrophy, transmitted from the mother, causes severe, even fatal hypotonia, weakness, and respiratory insufficiency in newborn babies. In addition to muscle disease, patients with myotonic dystrophy have cataracts, cardiac arrhythmias, testicular atrophy, and diabetes. Weakness is progressive. The biopsy shows atrophy of type 1 fibers, a profusion of central nuclei (normally myonuclei are under the sarcolemma), and ring fibers. None of these changes are diagnostic individually, but their combination strongly suggests myotonic dystrophy. Congenital myotonic dystrophy is characterised by small fibers with central nuclei, similar to centronuclear myopathy.

There are two genetic forms of myotonic dystrophy, DM1, and DM2. They are similar in most respects, except that in DM1 weakness is predominantly distal and in DM2 proximal. DM1 is caused by a CTG trinucleotide expansion in the DMPK (Dystrophia Myotonica Protein Kinase) gene on chromosome 19q13. In DM1, this gene is expanded over 37 CTG repeats. The more repeats, the more severe the dystrophy and the earlier the onset of symptoms. Thus, 100-150 repeats cause myotonia and cataracts, 150-1000 cause full blown myotonic dystrophy, and over 1500-2000 repeats cause neonatal myotonic dystrophy. As with other diseases caused by trinucleotide repeats, the onset of the disease is earlier with each successive generation (anticipation). DM2 is caused by a CCTG expansion of the ZNF9 (Zink Finger Protein 9) gene on 3q21. Neither mutation affects the coding portion of these proteins and it is not kown how these mutations affect muscle and other organs.

Further Reading

- Desgerre I, Mayer M. Leturcq F et al. Endomysial fibrosis in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a marker of poor outcome associated with macrophage alternative activation. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:762-73.PubMed

- Doorenweerd N, et al. Reduced Cerebral Gray Matter and Altered White Matter in Boys with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 2014 Jul 10. doi: 10.1002/ana.24222 PubMed.

- Liewluck T, Milone M. untangling the complexity of limb-girdle muscular dystrophies. Muscle and Nerve 2018;58:167-77. PubMed

Updated: November, 2018