MENINGIOMA

Meningiomas comprise about one third of primary BT and affect mostly adults, women more than twice as frequently as men. Ionizing radiation to the head is a risk factor for meningioma. Meningiomas may be located anywhere in the brain or spinal cord. About half of them arise over the cerebral convexities and one fifth at the sphenoid ridge. A few are intraventricular.

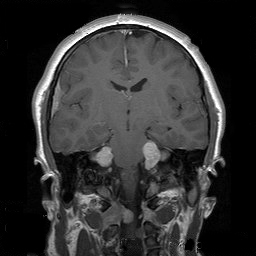

Meningiomas have an insidious clinical presentation with focal neurological findings (depending on location), seizures and signs of increased intracranial pressure. Many are incidental findings on brain imaging. On MRI, they appear as dura-based homogeneously enhancing, circumscribed lesions.

Meningioma |

Meningioma |

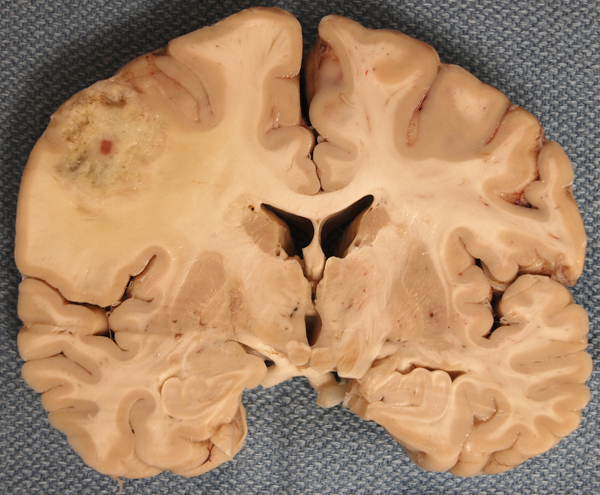

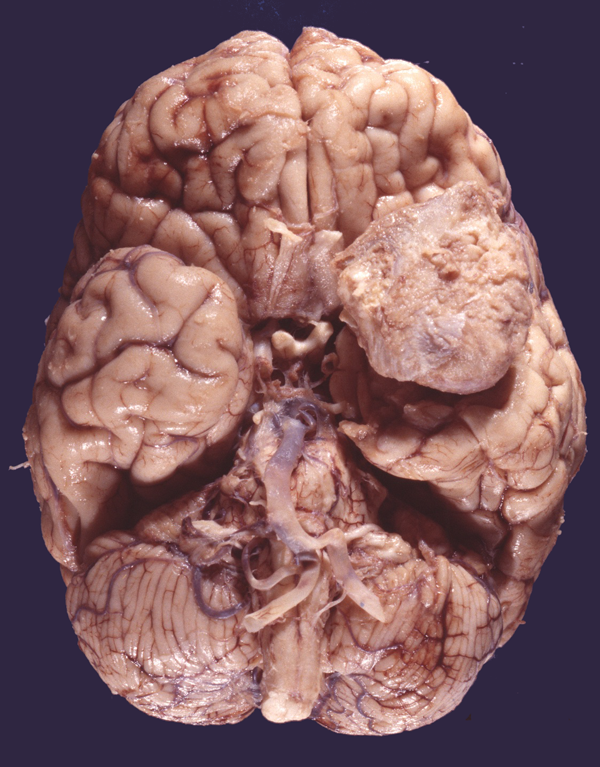

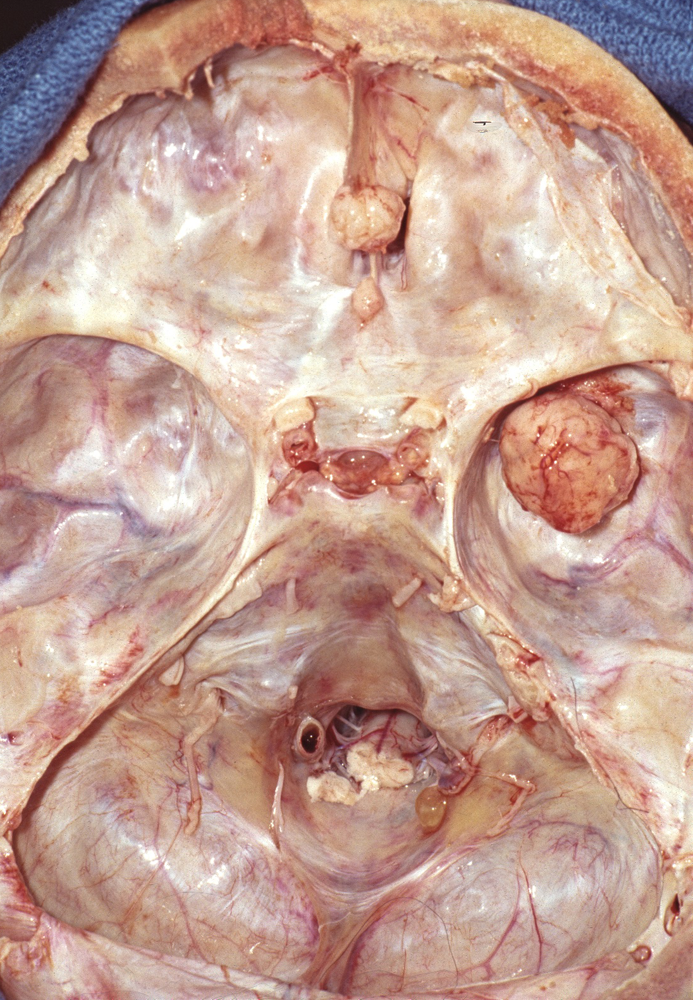

Dura-based meningioma |

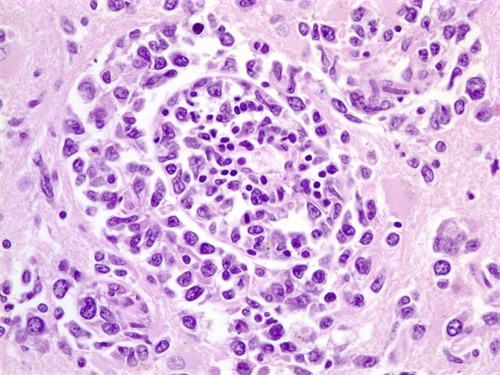

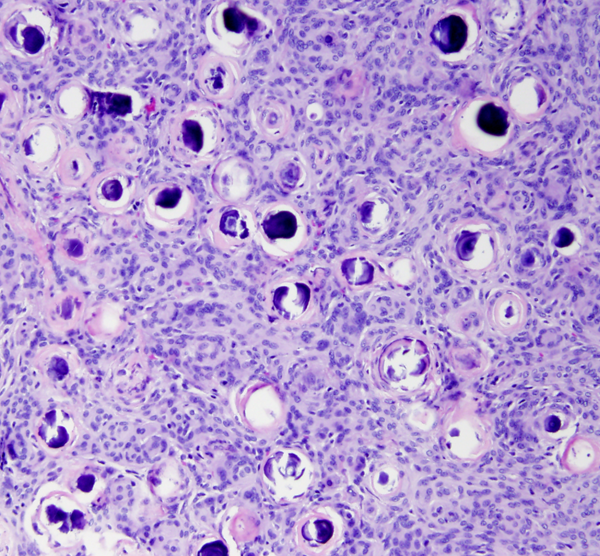

Transitional meningioma |

Fibroblastic meningioma |

Psammomatous meningioma |

On gross examination, meningiomas may be attached to the dura, though they do not arise from the dura per se. They are extra-axial tumors and most displace brain tissue without invading it. Some meningiomas grow flat on the surface of the brain. Meningiomas tend to infiltrate overlying bone, which is thickened (hyperostosis). This peculiar phenomenon does not indicate malignancy.

Meningiomas arise from arachnoidal cells. Microscopically, they have a variety of appearances on the basis of which they have been classified into several histological types. Meningothelial meningiomas are composed of diffuse masses of arachnoidal-like cells. In transitional meningiomas, tumor cells are arranged in whorls with hyalinized and calcified centers that are called psammoma (sand) bodies because they resemble tiny grains of sand. Fibroblastic meningiomas are composed of fascicles of fiber-like cells with abundant interstitial collagen. Meningothelial, transitional, and fibroblastic are the most common histological subtypes of meningioma but there are many more. Many meningiomas are histologically mixed. The tumor cells are positive for epithelial membrane protein. Some meningiomas express progesterone receptors resulting in accelerated growth during pregnancy.

Most meningiomas (80-85%) are benign (WHO grade I) and grow slowly. Because they are extra-axial, complete resection is possible in many of them and may be curative. Incomplete excision is followed by recurrence. Postoperative survival averages 12 to 15 years. 15-20% of meningiomas are WHO grade II (atypical meningioma). These tumors have increased mitotic rate and invade the brain. Additionally, they display atypical histological features such as increased cellularity, small cells, a diffuse patternless cellular growth, and necrosis. The clear cell and chordoid subtypes are also grade II. Atypical meningiomas grow more rapidly and are more prone to recur after surgical resection. A small proportion of meningiomas display overt cellular anaplasia and are classified as grade III (anaplastic or malignant meningioma). The papillary and rhabdoid subtypes are also grade III.

The majority of meningiomas show loss of the entire chromosome 22 or 22q. The latter contains the NF2 tumor suppressor gene, merlin. Meningiomas, especially of the fibroblastic type, are one of the BT seen in BANF. In BANF patients, meningiomas arise at a young age and may be multiple. Meningiomas also express female sex hormone receptors, explaining their rapid growth during pregnancy.

SCHWANNOMA

Schwannomas arise most often in cranial and spinal nerve roots and peripheral nerves but can occur anywhere, including in the brain and in the ventricles. Ninety percent of schwannomas arise in the vestibular division of the 8th nerve root (vestibular schwannoma, cerebellopontine angle tumor). Other cranial nerves are less frequently involved. Most Schwannomas are solitary. Bilateral vestibular or multiple Schwannomas are the hallmark of NF2. Other cranial nerves are less commonly involved. Vestibular schwannomas cause hearing loss, dizziness and tinnitus. The incidence of vestibular schwannoma has increased in recent years mainly because of increased use and accuracy of imaging, and many cases are found incidentally when MRI is performed for unrelated reasons. Schwannomas are extra-axial, circumscribed and encapsulated and range from small and solid to large, irregular, cystic, and hemorrhagic masses. They do not invade, but rather displace the brainstem and spinal cord as they grow. Microscopically, they consist of fascicles of spindle cells that are arranged in palisades. Less frequently they form a loose reticular pattern. They are benign, slow-growing tumors, and cause symptoms by compression.

NEUROFIBROMA

Neurofibromas are WHO grade 1 peripheral nerve tumors composed of a mixture of Schwann cells and fibroblasts. Multiple neurofibromas are characteristic of NF1. Cutaneous neurofibromas may be nodular or diffuse. Intraneural neurofibromas cause a fusiform enlargement of the nerve (or spinal root) in which they arise and may involve long segments of peripheral nerves. Such tumors are called plexiform neurofibromas-from a Greek word that means braid. Microscopically, their spindle cells are loosely arranged in a wavy pattern in a fibromyxomatous stroma. Residual axons and myelin may be mixed with tumor cells.

CRANIOPHARYNGIOMA

Suprasellar epidermoid cyst |

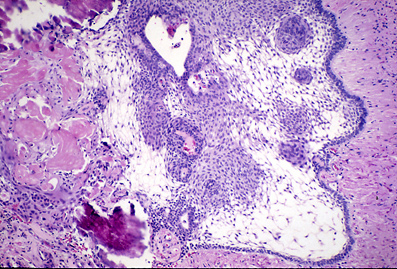

Craniopharyngioma |

Craniopharyngioma |

Craniopharyngioma. Cholesterol crystals. |

Craniopharyngiomas are most frequent in children and adolescents. They are suprasellar, similar to the illustrated epidermoid cyst, and are thought to arise from epithelial remnants of Rathke's pouch that are trapped in the pituitary stalk. Alternatively, they may represent a form of teratoma. They grow slowly and damage the hypothalamus, compress the optic chiasm, and block the third ventricle, causing endocrine abnormalities, visual disturbances, and hydrocephalus.

Grossly, they show a mixture of solid and cystic areas. Microscopically, they are composed of sheets of squamous epithelial cells and keratin, set in a loose connective tissue stroma. Islands of keratin often calcify. Water accumulating in the central portion of the epithelial islands causes them to loosen, creating an appearance that resembles adamantinoma. Cholesterol crystals, formed from break down of keratin, float in the greasy fluid that fills the cysts giving it an iridescent appearance. Cysts, calcification, and the suprasellar location are the criteria for the radiological diagnosis of craniopharyngiomas. Other common suprasellar tumors are pilocytic astrocytoma and germ cell tumors.

HEMANGIOBLASTOMA

Hemangioblastomas are infrequent vascular tumors of the CNS. About 75% are sporadic and the rest are familial and occur in the background of the autosomal dominant von Hippel Lindau disease. Sporadic tumors are solitary and affect most frequently middle aged adults but may occur at any age. Familial hemangioblastomas involve children and young adults. They tend to be multiple (cerebellum, spinal cord, retina) and are frequently accompanied by a variety of other tumors and nonneoplastic lesions that characterize VHL disease (cysts and clear cell carcinomas of the kidneys, pheochromocytomas, cysts of the liver and pancreas, pancreatic tumors, epididymis cysts, cystadenomas of the broad ligament and endolymphatic sac tumors of the middle ear). The most common location is the cerebellum. Typically, cerebellar hemangioblastoma is a mural nodule within a cyst. In the spinal cord, it may be a solid intramedullary lesion associated with a syrinx.. Hemangioblastoma is a benign tumor which consists of numerous delicate capillaries set in a background of clear foamy cells.

CEREBRAL LYMPHOMA

CNS lymphoma in absence of systemic lymphoma (Primary CNS Lymphoma-PCNSL) is a rare tumor thought to arise from indigenous brain histiocytes (microglia) or from rare lymphocytes that are normally present in the meninges and around blood vessels. PCNSL may develop in patients with intact immune system but affects with higher frequency immunocompromised individuals such as patients with organ transplants. In the past, it was the most frequent primary brain tumor in AIDS patients but its frequency in this group has decreased dramatically with highly active antiretroviral therapy. PCNSL usually presents with focal neurologic deficits, and appears as enhancing, T2-hyperintense, frequently multiple and bilateral white matter lesions, which may involve the corpus callosum. Most cases are supratentorial but a few involve the cerebellum, brainstem and spinal cord. Primary vitreoretinal lymphoma occurs in the same settings as PCNSL, and PCNSL may involve the eye in some cases. The diagnosis is usually made by stereotactic needle biopsy. PCNSL is typically a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). The tumors that arise in immunocompromised patients are EBV-positive. The tumor cells form dense perivascular sheaths or diffuse masses. Meningeal spread is very common, and some PCNSLs arise in the subarachnoid space. Corticosteroids induce apoptosis in PCNSL cells that may be so profound that the tumors disappear (vanishing lymphoma). In addition to DLBCL, other types of lymphoma, including T-cell lymphoma and Hodgkin's disease rarely arise primarily in the CNS. While leukemia, especially ALL, frequently spreads to the subarachnoid space, systemic lymphomas involve the CNS very rarely, but this possibility needs to be ruled out when a PCNSL is diagnosed.

METASTATIC TUMORS

Meningeal carcinomatosis Meningeal carcinomatosis from carcinoma of the breast. Glandular carcinoma formations in the subarachnoid space. |

Metastatic tumors account for the majority of BT that are seen in general community hospitals. Brain metastases are found at autopsy in 14-37% of malignant tumors of adults and are less frequent in pediatric tumors. The most common primary tumors that cause brain metastases are carcinoma of the lung, breast carcinoma, and melanoma. Metastatic tumors are frequently multiple. They arise by hematogenous spread and most are located in the supratentorial compartment with only 10% in the posterior fossa. They present with headaches, mental status change, focal deficits, and seizures. Metastases are usually clinically detected on average 12 months after the primary is diagnosed but in some cases they may be diagnosed at the same time. Meningeal carcinomatosis (diffuse spread of tumor in the subarachnoid space) is seen in 4% to 8% of metastatic BT and is more common with carcinoma of the lung, carcinoma of the breast, and acute lymphoblastic leukemia. It causes headache, drowsiness, cranial nerve deficits, spinal root pain, and paresthesias. The CSF in meningeal carcinomatosis shows high protein, low glucose, and a few lymphocytes. The often insidious onset of symptoms and the CSF findings suggest mycobacterial meningitis, especially if the primary tumor is too small to be detected. Cytological examination of CSF reveals tumor cells.

Extraneural metastases (ENM) of primary BT are rare and the reasons for this are not clear. They are seen in glioblastoma and other high grade gliomas, medulloblastoma, and ependymoma. The incidence of ENM in high grade gliomas has been estimated to be less than 2%. ENM occur usually after surgery, when tumor cells accidentally get into vessels. Spontaneous ENM is extremely uncommon. The most frequent metastatic sites are the pleural cavity, lung, lymph nodes, vertebrae, and liver.

THE EFFECTS OF BRAIN TUMORS

The local effects of BT are loss of function (focal deficits) and seizures. An insidious onset of seizures in an otherwise healthy person strongly suggests a BT. The general effects of tumors have to do mainly with increased intracranial pressure. Increased intracranial pressure is caused by a) the mass of tumor added to the brain, b) hydrocephalus due to obstruction of CSF circulation and c) cerebral edema, i.e., accumulation of fluid in the interstitial space around the tumor. Fluid leaks from tumor vessels that do not have dense junctions as normal brain capillaries do. With some exceptions, high vascularity is a feature of rapidly growing tumors. Consequently, cerebral edema is seen in malignant BT (GBM, medulloblastoma, cerebral lymphoma, metastatic tumors). Hydrocephalus is a common feature of posterior fossa tumors, the majority of which are seen in children. Cerebral edema and hydrocephalus are life-threatening complications and may cause displacements (herniations) and compression of brain structures with lethal effects (See Chapter 4: Craniocerebral trauma and increased intracranial pressure).

Further Reading

- Giannini C, Dogan A, Salomao DR. CNS Lymphoma: A Practical Diagnostic Approach. L Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2014;73-478-94 PubMed.

- Tosoni A,Ermani M, Brandesa AA. CNS Lymphoma: The pathogenesis and treatment of brain metastases: a comprehensive review. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology PubMed

- Buerki RA, Horbinski CM, Kruser T et al. An overview of meningiomas. Future Oncol 2018; (21):2161-77PubMed

Updated: May, 2020